COVID's Drastic Toll on Women's Participation in Labour Force Continues

Written by Dawn Desjardins and Carrie Freestone

Published on December 3, 2020

minute read

Share:

Recent data signal a troubling trajectory. Midway through 2020, we warned that Canadian women had paid — and would continue to pay—a heavier price than men during the pandemic-induced recession. In a matter of weeks during the spring, COVID-19 rolled back the clock on three decades of advances in women's labour-force participation, setting Canada's economy up for a slower recovery than might otherwise be the case. Despite notable rebounds in overall employment and GDP in recent months, the pandemic continues to cloud the future for many industries in which women had significant representation. What's more, the pandemic has made the family responsibilities that women typically shoulder that much heavier.

That's set up a divergent, and troubling, trajectory that's seen Canadian women continue to retreat from the workforce even as Canadian men more than make up for ground lost early in the pandemic.

Key Findings

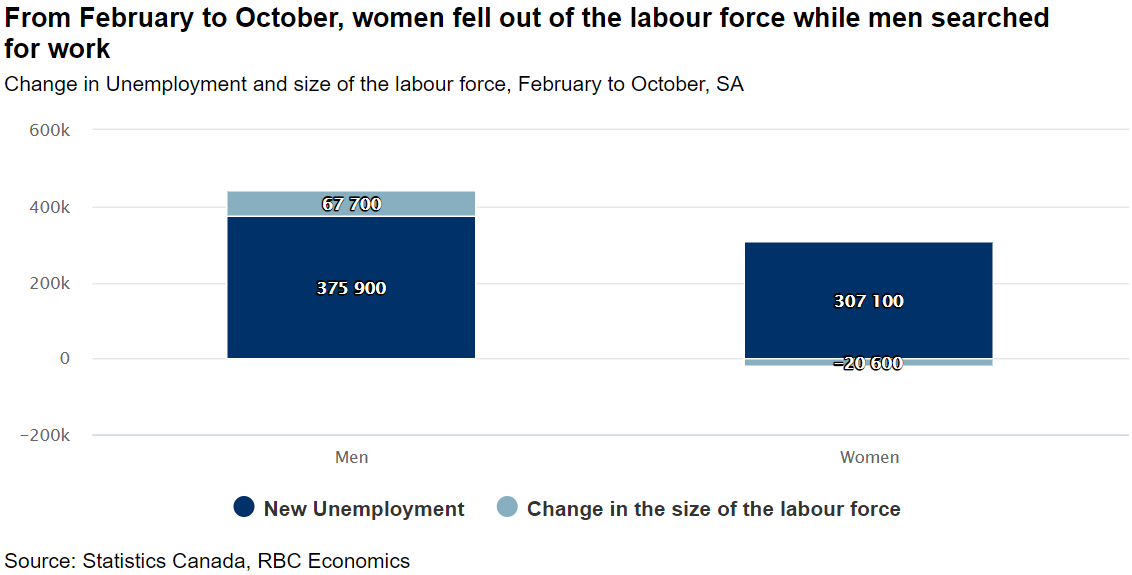

- Between February and October, 20,600 Canadian women fell out of the labour force while nearly 68,000 men joined.

- Women in two key cohorts are exiting the labour force faster: women aged 20-24 and 35-39.

- Women are more exposed to hardest-hit industries and overrepresented in industries less conducive to working remotely.

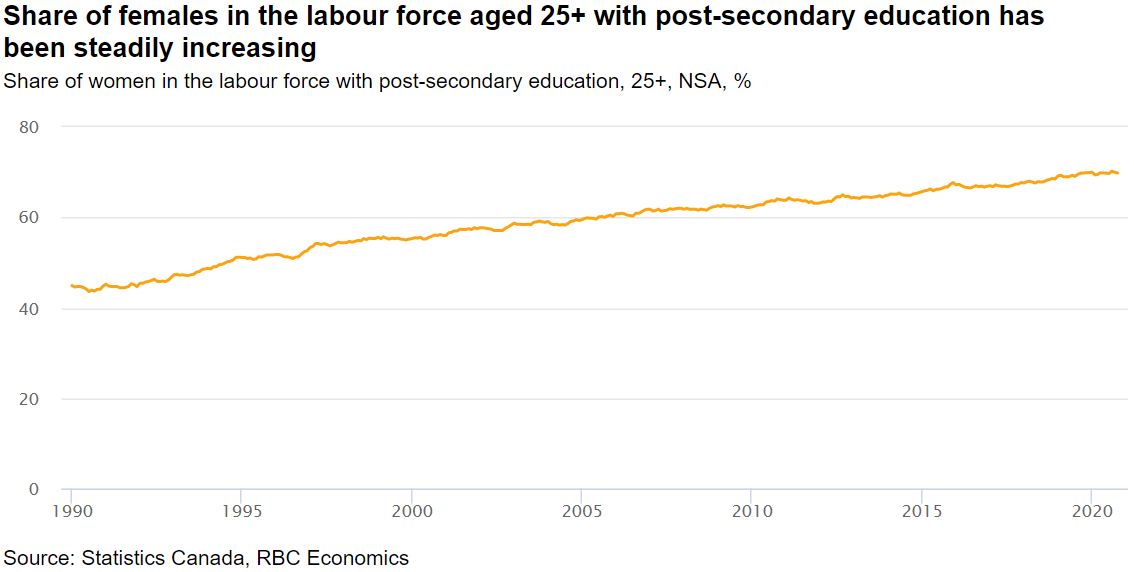

- Women exiting the labour force face the risk of an erosion skills which may further exacerbate the gender wage gap that existed prior to the pandemic.

Women are leaving the labour force even as men rejoin it

Between February and April, more than 3 million Canadians lost their jobs, roughly half of them women. As of October, nearly 2.4 million of those people had re-gained employment, half of them women. However, not all labour-force outcomes are as evenly divided between the genders. Between February and October, 20,600 women fell out of the labour force, even as 68,000 more men joined it. Indeed, the number of women who are out of the labour force has increased 2.8% since February.

From February to October, Canadian women accounted for ~64% of the increase in the number of people who are not in the labour force, that is, people who have lost their jobs, are not temporarily laid off, and are not looking for work. When men lost their jobs, the majority actively sought out employment (meaning that they were considered `unemployed'). Meanwhile, a sizeable portion of women chose not to (they were considered `out of the labour force').

Why have women retreated even as men exceed pre-COVID participation levels?

- Women are more likely to occupy industries that have been slower to recover and are also more exposed to a potential for lockdowns.

- Women's ability to work from home may be more limited compared to men, especially when taking into account the larger role they play in fields including hospitality, retail and the arts.

- The pandemic has made women's family-care responsibilities more onerous: some daycares are operating with smaller class sizes , and many school-aged children are spending some or all of their school time in e-learning settings. The situation, while temporary, may be forcing more women to choose not to work outside the home.

The pattern of women exiting the labour force even as men rejoin it makes this recession different from previous ones. In the 2008-2009 recession, men absorbed more job losses, and were slower to re-enter the workforce.

The nature of women's occupations and the impact of COVID-19

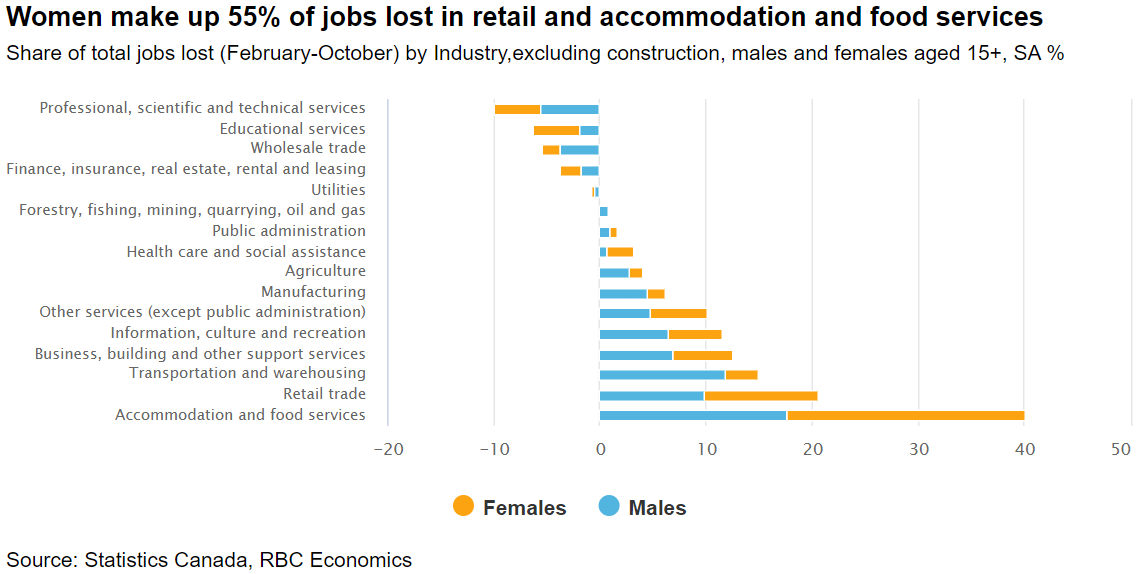

Canadian women were more likely to work in customer-facing positions and in industries, like accommodation and food services, that were hard hit by the recession. Where women worked, along with their greater tendency to work part-time, explains roughly two-thirds of women's job losses.

In October, the accommodation and food services industry saw its first month of job losses since April, as the temporary boost from local summer travel and outdoor dining evaporated. Of the 48,000 workers in this industry who lost their jobs in October, ~80% were women. In fact, women account for nearly twice the share of the decline in labour force participation in this industry as males. Fears of a second surge likely factored heavily in their decision to remain out of the labour force.

Meanwhile, males have benefited from some pandemic-driven labour trends. From February to October, the professional, scientific, and technical services industry hired 55,000 workers as e-commerce activity surged. Three-quarters of these positions were filled by men.

What's more, what one does has bearing on where one can perform the work. Men are overrepresented in professional, scientific, and technical services and business, building and other support services (including management of companies and enterprises)—sectors that are more conducive to working remotely. Restaurants, bars and retail, where women have a heavy presence, don't offer that flexibility.

A Tale of Two Generations

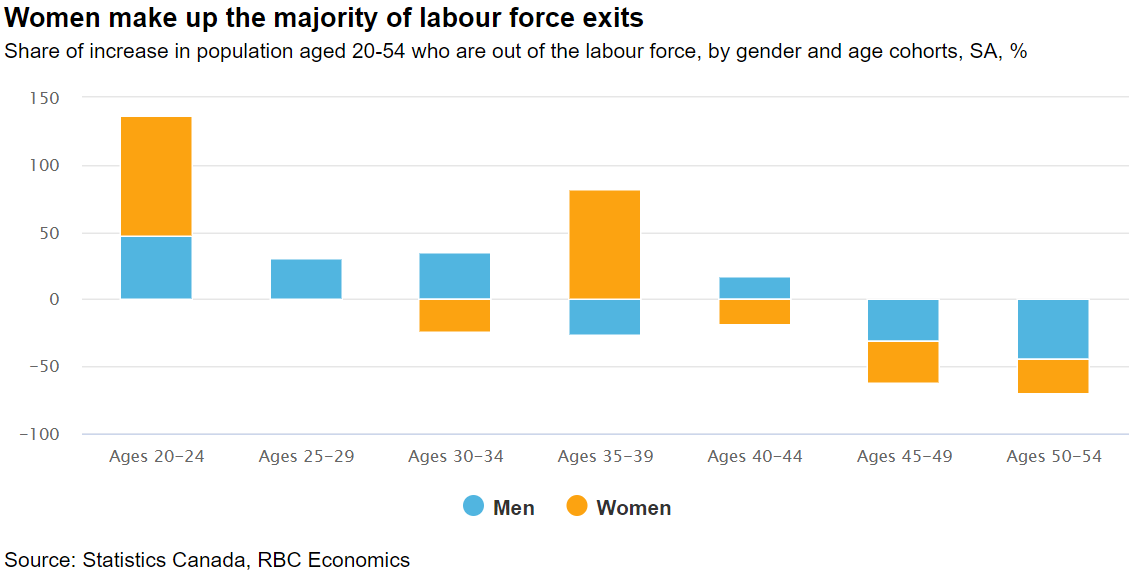

Among women, two key age cohorts are leaving the workforce in more notable numbers: young women, and women most likely to be rearing young children.

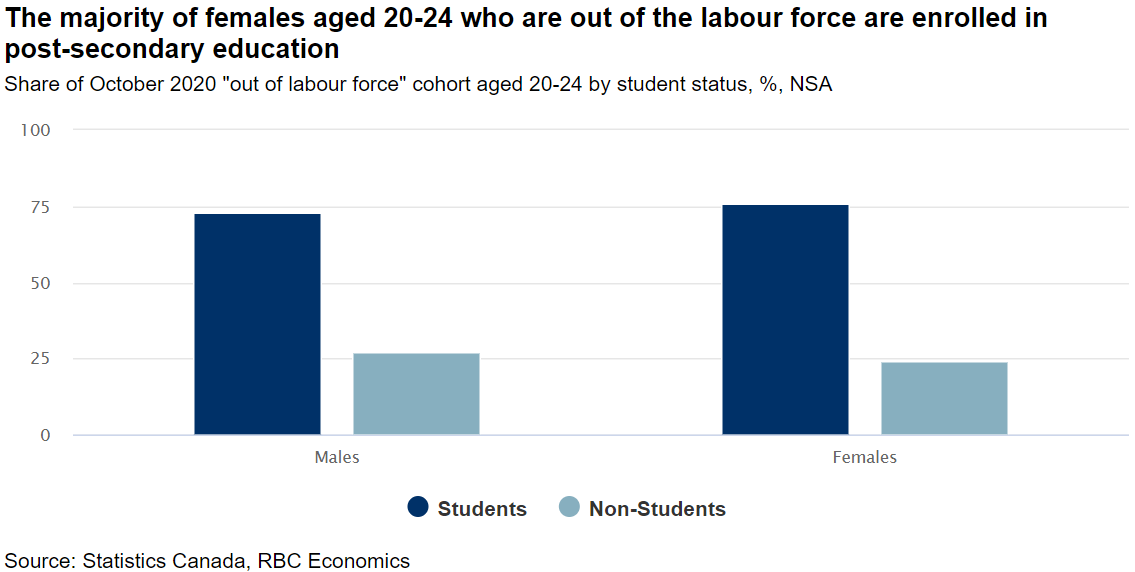

The size of the labour force for women aged 20-24 shrank roughly 4.6% from February to October, even as young men's labour-force participation turned positive. That isn't particularly surprising. In Canada today, young women are more educated than their male contemporaries, and over three-quarters of women aged 20-24 who were out of the labour force as of October were enrolled in post-secondary education. Their exit implies that many young women are choosing to return to school or re-skill in the face of a recession.

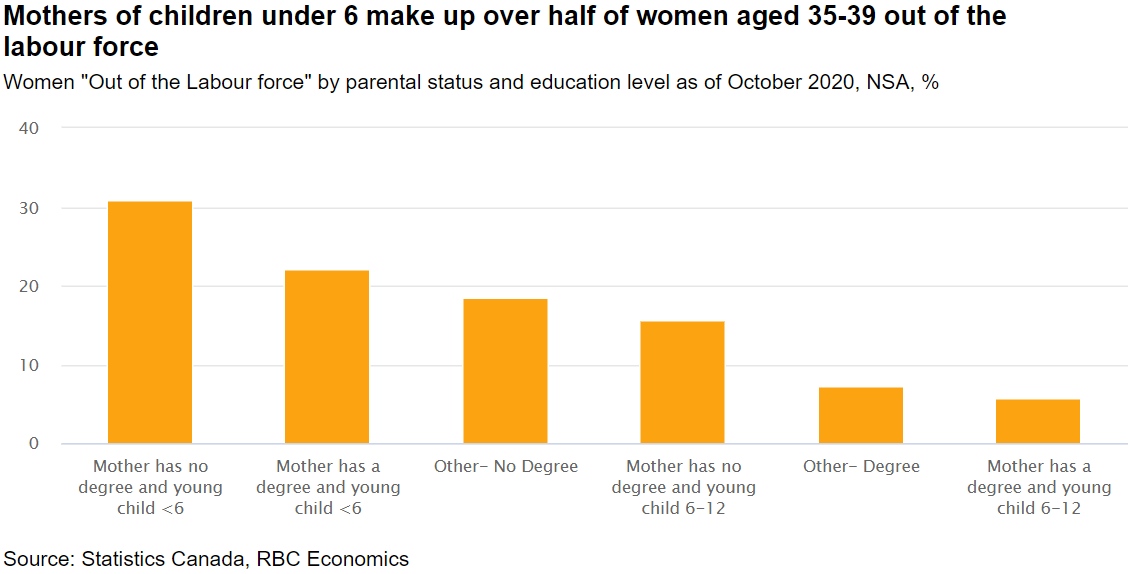

Since young Canadian women are positioning themselves for a post-crisis working life, their exit from the workforce is less concerning than that of women aged 35 to 39, who are exiting the labour force in droves. While men in this cohort have also seen a drop in participation, it's been more pronounced among women. Indeed, roughly half of women in this cohort who have lost their jobs since February have not searched for work. The explanation appears to be motherhood. Women with children under 6 made up 41% of the labour force in February, but account for two-thirds of the ensuing exit from the labour force. And this trend does not differ based on educational attainment, since both mothers with degrees and those without are opting to focus on child-rearing responsibilities at home.

Conclusion

COVID-19's second wave, and renewed restrictions on economic activity, won't deliver a shock of the same magnitude as the one that struck Canada last spring. For one, sectors including retail have begun adapting to a more digital mode of operating. Nevertheless, any developments that prolong the struggles of certain industries and keep more children at home are likely to delay women's return to the labour force. That delay could have far-reaching implications for narrowing the gender wage gap and for facilitating the ability of women to acquire the skills they will need in an economy in the midst of significant transition.

RBC Direct Investing Inc. and Royal Bank of Canada are separate corporate entities which are affiliated. RBC Direct Investing Inc. is a wholly owned subsidiary of Royal Bank of Canada and is a Member of the Canadian Investment Regulatory Organization and the Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Royal Bank of Canada and certain of its issuers are related to RBC Direct Investing Inc. RBC Direct Investing Inc. does not provide investment advice or recommendations regarding the purchase or sale of any securities. Investors are responsible for their own investment decisions. RBC Direct Investing is a business name used by RBC Direct Investing Inc. ® / ™ Trademark(s) of Royal Bank of Canada. RBC and Royal Bank are registered trademarks of Royal Bank of Canada. Used under licence.

© Royal Bank of Canada 2025.

Any information, opinions or views provided in this document, including hyperlinks to the RBC Direct Investing Inc. website or the websites of its affiliates or third parties, are for your general information only, and are not intended to provide legal, investment, financial, accounting, tax or other professional advice. While information presented is believed to be factual and current, its accuracy is not guaranteed and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the author(s) as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by RBC Direct Investing Inc. or its affiliates. You should consult with your advisor before taking any action based upon the information contained in this document.

Furthermore, the products, services and securities referred to in this publication are only available in Canada and other jurisdictions where they may be legally offered for sale. Information available on the RBC Direct Investing website is intended for access by residents of Canada only, and should not be accessed from any jurisdiction outside Canada.

Explore More

Economic Outlook: Uncertainty is Here to Stay, So What's Next?

Takeaways from the Economic Club of Canada’s Annual Event

minute read

3 things: Week of December 15

What the Inspired Investor team is watching this week

minute read

Year in Review: Tariffs, Tech, Rates and More

Looking back at some major stories of 2025, plus lessons investors can take into the new year

minute read

Inspired Investor brings you personal stories, timely information and expert insights to empower your investment decisions. Visit About Us to find out more.